After Ophelia (2025)

We are all written by others, then rewritten by their machines.

Overview · Works · Process · Supporting Texts · Exhibitions

I googled myself once and found information that wasn’t right. Some outdated, some completely wrong. They were written by others and preserved in archives I have no access to. When AI systems summarize me now, they cite these errors and I've become what's been said about me.

In Shakespeare's play, Ophelia speaks fewer than 200 words, yet entire essays, paintings, films, and now AI-generated analyses claim to explain who she really was. John Everett Millais' 1852 painting gave her a face most people still imagine. Academic discourse gave her symbolic weight. YouTube video essays and Reddit threads continue the cycle. Now, when you search "Ophelia," AI synthesize all of this into confident summaries, each generation of technology adding another layer between the character and whoever she might have been.

Recently, Taylor Swift released "The Fate of Ophelia" on her new album, extending this pattern into pop culture. Ophelia remains a vessel for other people's meanings, her story endlessly rewritten by whoever holds the microphone, or the algorithm.

After Ophelia traces how a person's image is built, stabilized, and automated by others. It asks: when everyone tells your story for you, what remains that's actually yours?

Overview

Ophelia, Retold (2025)

Ophelia, Retold text sources:

Shakespeare, Hamlet

YouTube: World’s Greatest Paintings S01 E09

YouTube: Jen Chan

YouTube: Dr Scott Masson

Reddit r/Shakespeare (Comprehensive-Act-13)

Elaine Showalter, “Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticism”

Christine Riding, John Everett Millais (Tate, 2006)

Reddit r/ArtHistory (natalielynne)

Single‑channel video with 3D‑rendered visuals and AI‑generated voice, incorporating sourced text from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, academic writings, and online commentaries of Ophelia.

Single-channel video, 4K (3840×2160), 16:9, 1 min 17 sec loop, MP4

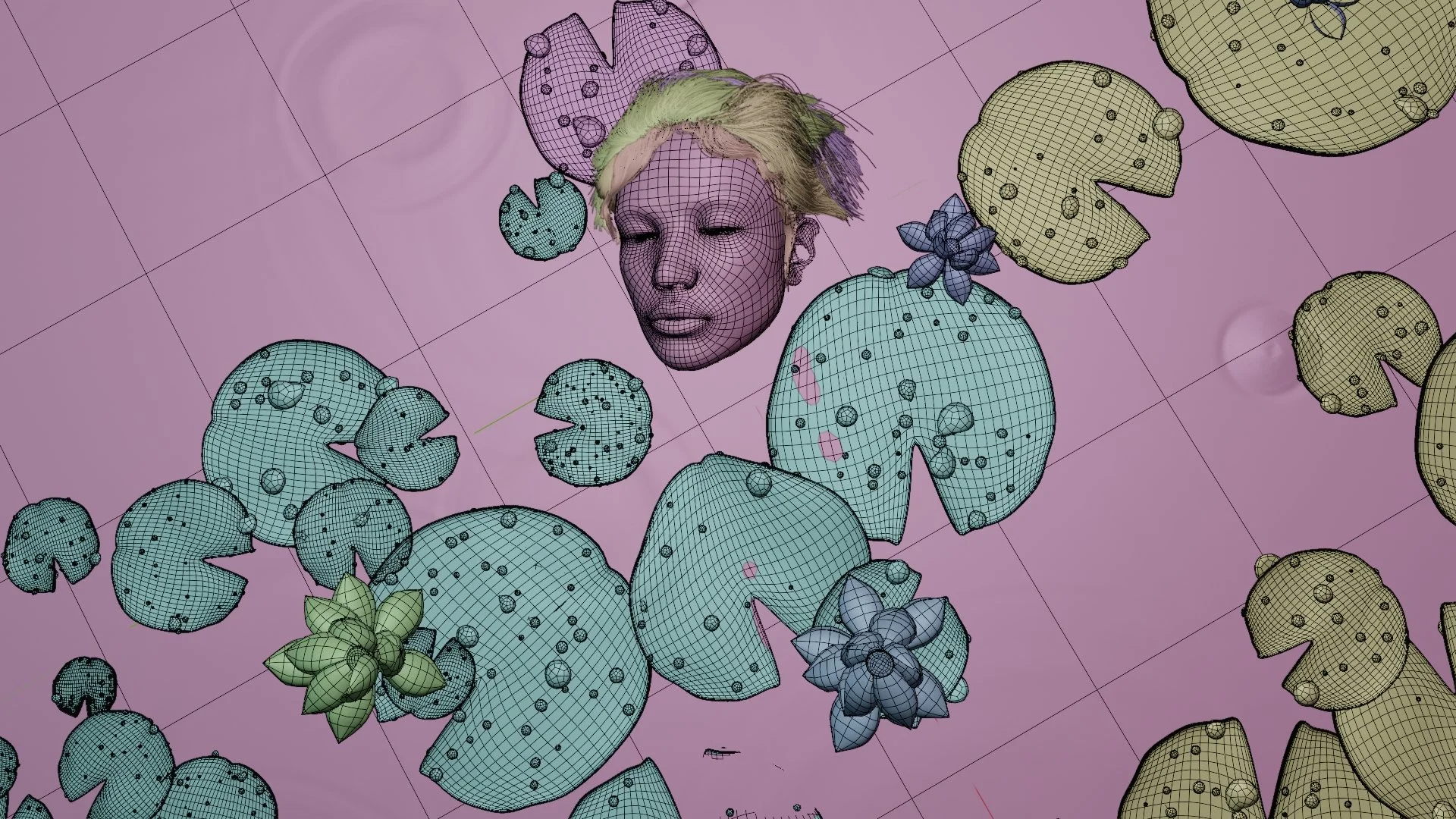

Ophelia, Reassembled (2025)

Single‑channel video collage composed of 3D‑rendered imagery and AI‑generated fragments, layered with digital mesh overlays and simulated textures.

Single-channel video, 4K (3840×2160), 16:9, 15 sec loop, MP4

Process

Both works show how representation becomes a kind of erasure.

I followed how Ophelia has been passed from voice to voice, medium to medium, each time losing a bit more autonomy. Shakespeare's text became Millais' painting. The painting became the default mental image. That image became the basis for countless reinterpretations, academic and casual, each claiming insight into her madness, her victimhood, her symbolic function. Now AI systems scrape all of this and present it as objective knowledge.

In Ophelia, Retold, I gathered these fragments and let an AI voice speak them. The quotes come from their original sources. Some unchanged, others shifted in meaning simply by being placed beside new company, much like Ophelia herself. The 3D-rendered figure searches through space as though looking for herself inside this borrowed language.

Ophelia, Reassembled continues this through image rather than voice. I created initial 3D renders, then transformed them using AI image generation, deliberately leaving the process visible. The meshes, the digital artifacts, the moments where the illusion breaks - these aren't flaws but evidence. They show that every image of Ophelia is constructed, that authenticity was never an option.

Together, the works create a loop between being seen and being retold, between image and explanation, never quite resolving into a single stable truth.

Artist Statement

This work began with a personal experience of finding my own image misrepresented online, then discovering how quickly those misrepresentations calcify into accepted fact. Ophelia became the perfect historical parallel, a figure defined almost entirely by other people's interpretations, now endlessly recycled by algorithmic systems that treat all sources as equally valid.

The project doesn't propose to recover the "real" Ophelia, that person is irretrievable. Instead, it makes visible the mechanisms of her ongoing construction: the voices that claim to explain her, the images that claim to show her, the platforms that claim to know her.

In an age where AI can generate both images and explanations with equal fluency, the line between representation and fabrication has collapsed entirely. We are all, in some sense, becoming Ophelia. Written by others, then rewritten by their machines.

Supporting Texts

-

“There is no ‘true’ Ophelia for whom feminist criticism must unambiguously speak, but perhaps only a cubist Ophelia of multiple perspectives, more than the sum of all her parts.

The heroine of Hamlet has always been a blank screen on which generations of spectators have projected their own preoccupations. Each age constructs its own Ophelia, and each commentary becomes a mirror of its author’s assumptions.” -

“Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.

This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object — and most particularly an object of vision.” -

A text is made of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation.

But there is one place where this multiplicity is focused — the reader, not the author.

The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author. -

“That which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art.

What is really jeopardized when the authentic production of art is substituted by mechanical reproduction is the authority of the object.”

Exhibitions

After Ophelia will be shown at

SCENES: The Sensory and Constructed Image in the Digital Age

When: Nov 13–16, 2025 (VIP Nov 12)

Where: Digital Sector, Paris Photo 2025

Organizer: ArtVerse Gallery.